Working continuously for several months in the archives of the Venerable English College in Rome (VEC) has been a source of immense pleasure and intellectual growth. Not only because of the variety of materials available in the archive, but also because of its exceptional custodian, Professor Maurice Whitehead, whose vast knowledge of British Catholic history and generous support continuously facilitated my progress.

I knew that at the VEC I was going to find material on college drama (many play-texts, mostly in Latin, still survive), on musical practice, and elaborate devotional life. What I wasn’t expecting, however, were references to social dancing amongst the seminarians! For early modern moralists dancing was hardly ever harmless and even less so in a semi-enclosed space of a seminary. In Rome, however, even cardinals did not abstain from skipping, and, as we shall see, it was also a normal practice in the colleges, particularly during Carnival.

But before I share those intriguing records, I wanted to give you a short introduction to the English College, which some of you might not have heard of before, and briefly sketch how my research interests intersect with the College’s history. However, if you just want to read about the dancing seminarians, please scroll down to the second half of this post.

The Venerable English College in Rome was officially established in May 1579 by Pope Gregory XIII, although the repurposing of the declining English medieval hospice dedicated to the Most Holy Trinity and St. Thomas of Canterbury in Via Monserrato had already begun some years earlier. So alongside the hospice rose a seminary for English and Welsh students, who came to Rome to complete their higher education (philosophy and theology courses) at the Collegio Romano. Most students started their studies when they were around eighteen years old, although many joined later in life as well. Like most other national colleges in Rome, the English College was under Jesuit administration, and although rather small in comparison to the German and Hungarian College or the Roman Seminary, for example, the VEC was far from a marginal institution. It was the flagship English seminary, maintaining deep links with the Roman elite. Its patrons and protectors were of the highest calibre: think of cardinal nephew Filippo Boncompagni (1580-86), Cardinal Odoardo Farnese (1600-26), and after his death, Cardinal Franceso Barberini, the cardinal nephew of Pope Urban VIII (1626-1679).[1]

The College was generously supported by Papal endowments, so those students, who upon entering were willing to enter holy orders, studied for free. On the other hand, student commoners or convictors, as they were called, who simply wanted to obtain a degree from Collegio Romano, were also admitted, but their expenses had to be met by themselves and their families. After completing their studies, the new priests were expected to take the missionary oath and return back to Britain, where they faced a difficult task.

After the excommunication of Protestant Queen Elizabeth I by Pope Paul V in 1570, the English Crown gradually adopted stricter legal measures against Catholics and priests in particular. The 1585 act against Jesuits and seminary priests banned Catholic priests from the country under pain of death and labelled them as traitors. Missionaries could only return back home in secret; if discovered and seized on English soil, they could be accused of treason and executed simply because they were ordained priests. English and Welsh seminarians training in Rome and other colleges in Spain and the Low Countries accepted this risk and during their period of education cultivated a sense of honour and pride in their commitment to re-Catholicising England. For the seminarists, martyrdom was a real possibility, so they were encouraged to contemplate and celebrate during their training.

I am drawn to the VEC in my research because, being placed at the heart of the global Catholic Church, it was and still is one of the most important English Catholic institutions outside Britain. What and how things were done at the College in Rome mattered for what and how things were done among Catholics in England and Wales. The seminarians’ Roman formation did not entail only formal education and a strict daily routine of religious devotion and self-examination. VEC was also a place of recreation and hospitality (particularly during Carnival and the feasts of the Most Holy Trinity and St. Thomas of Canterbury), of splendid musical and dramatic practice, of inculturation and cultural mediation. English national character and English customs mattered at the VEC, but so did Roman ways, which the students experienced there and often eagerly adopted.

Therefore, we can also see the English College (as well as other national colleges in Rome) as a conduit for Roman Baroque – Baroque as a ‘style of life’ to paraphrase Peter Rietbergen.[2] The profoundly performative Baroque way of living nurtured a relentless need to display, embody, and make apparent to the senses the otherwise private beliefs and emotions. Such public display was not perceived as insincere ostentation, but rather essential to shaping an individual’s self and society as a whole: it made apparent and strengthened both personal zeal and social unity. One of most potent and colourful expression of this way of life were religious festivals and devotions which took place in Roman streets, halls, and churches. Such spectacular public expressions of faith were mostly impossible to experience in England at the time.

To what extent, I wonder, did the English and Welsh students internalise these cultural imperatives? And how did they deal with a comparable dearth of visual and auricular splendour when after years of study abroad they swapped the Eternal City for Lancashire or Yorkshire?

It’s difficult for us today to soundly address these questions because we lack detailed first-hand accounts of students’ personal experiences both at the College and later on the mission. For example, no private diaries of seminarians or priests survive from the 16th or 17th centuries (if you know of any, please let me know!). But the points are still worth pursuing, and I am determined to pull together available sources and learn as much as I can about performance culture at the VEC, and consider how it might have impacted the missionary activities of the alumni back home.

In early modern Rome, the Carnival season (which takes place in February/March) lasted from Sexagesima (the second Sunday before Ash Wednesday) to Shrove Tuesday. While this pre-Lent period was to some extent devoted to spiritual self-reflection, it was first and foremost a time of self-indulgence, of topsy-turvy feasting, masquerading, gaming, and entertaining. The two weeks before Ash Wednesday were also an unofficial Roman theatre season: plays, operas, and jousts were put on by the nobility in private halls and city squares, and spiritual and edifying subjects were staged by the students of numerous colleges, including those of the English College. The college plays were generally meant to challenge the overindulgence ruling the city in this period, and were part of the so called carnevale santificato (‘sanctified Carnival’ as opposed to ‘profane Carnival’). They took the popular means of entertainment and made them vehicles for spiritual growth. But that did not always save them from scandal.

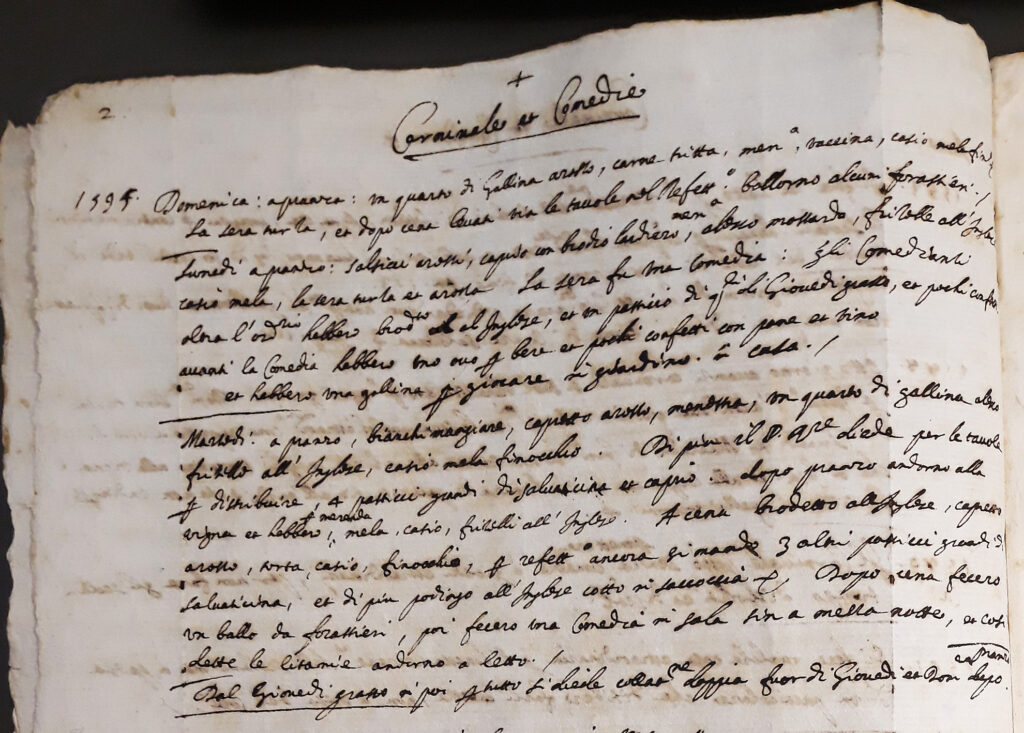

During carnival of 1595, more or less ‘sanctified’ feasting, playing, and dancing took place at the English College. Records of those entertainments are found in a remarkable document entitled Festa mobilia et extraordinaria per annum (Movable and extraordinary feasts during the year) compiled by Father Nathaniel Southwell, an alumnus of the College, who worked at the VEC from 1627 as father minister and later also as procurator. As minister and procurator, Southwell was interested in the past College customs on feast days and was keen to note down the developments, practices, and expenses throughout the years (from 1583 to 1622). The College must have used this document as a reference point, a list of memoranda and precedents that could be cited when planning future celebrations at the College.

The document opens with the heading of Carnivale et Comedie (Carnival and comedies). Dancing is explicitly mentioned only during Carnival of 1595 and 1597. For 1595 celebrations, details are given for the whole of Carnival season starting with Sexagesima Sunday. During the last three days, Shrove Sunday, Monday, and Tuesday (5th to 7th of February), festivities intensified. Southwell writes:

Domenica: apranzo: vn quarto di Gallina arosto, carne tritta, mon[gan]a, vaccina, casio mela fin[occhi]o & la sera turta, et dopo cena leuati via le tauole nel Refett[ori]o. ballorno alcuni forastieri.

(Sunday, lunchtime: a quarter of a roasted hen, minced meat, veal, beef, cheese, apples, fennel, and a cake in the evening, and after dinner, tables were removed in the refectory, some guests danced.)

AVcAU, Scr. 6/25/11, p. 2

On Monday, feasting continued and a play was performed. Those students that were acting in the comedy got extra food allowance:

brod[et]to al Inglese, et vn pasticcio di q[ue]li di Giouedi grasso, et pochi confetti. auanti la Comedia habbero vno ouo p[er] bere et pochi confetti con pane et vino et habbero vna gallina p[er] giocare in giardino in casa.

(English soup, one of the Shrove Thursday pies, and some sugared almonds. Before the comedy they had an egg to drink and a few sugared almonds with bread and wine, and they got a hen to play for in the college garden.)

AVCAU, Scr. 6/25/11, p. 2

Tuesday was the big day, a culmination of the season. On top of an already abundant lunch which included blancmange, roasted goat, English-style pancakes, and always present cheese (most likely pecorino) with apples and fennel, Father Rector Girolamo Fioravanti divided among the students four ‘pasticci grandi di saluaticina et capri[n]o’ (large game and goat pies). The College spend the afternoon in their vineyard and returned to the city for another grand dinner. Extras were again distributed: ‘3 altri pasticci grandi di saluaticina, et di piu podingo all’ Inglese cotto in saccoccia’ (another three large game pies and English pudding cooked in a casing). Further entertainments followed; dancing, a comedy, and then litanies before bedtime:

Dopo cena fecero vn ballo da forastieri, poi fecero vna Comedia in sala sin a mezza note, et cosi dette litanie andarno a letto.

(After dinner, they did a dance for the guests, then they did a comedy in the hall until midnight, and so, after saying the litanies, they went to bed).

AVCAU, Scr. 6/25/11, p. 2

If on Sunday, those dancing in the College refectory were only forestieri, that is, the strangers, or outsiders, in other words, the College guests (most of them probably English), Southwell’s phrasing about Tuesday festivities seems less explicit. One could literally translate ‘vn ballo da forestieri’ as a type of dance. Could it be that at least the Shrovetide ball was not meant for the guests only, but for the students as well?

In isolation, these records paint a picture of a harmonious and open community, which in spite of its rigorous everyday routine is capable of honest and tranquil conviviality. We get a sense that there is a mutual trust between boarders and their Jesuit superiors, who are happy to grant licence for exceptional recreation at this special time, and that the outsiders are warmly welcomed within the College walls. Students, we can imagine, appreciate all the extra treats and the late evening entertainments in the company of guests. But not everything was as perfect as it seems.

Since its establishment, the English College was plagued with divisions and tumults. Conflicts in the College often reflected the existing tensions within the English Catholic community at home. These conflicts were often drawn along the lines dividing the secular and regular clergy (Jesuits in particular). In order to demonstrate their loyalty to the English Crown, some secular clergy were capable of fierce anti-Jesuit and anti-Spanish sentiments; Jesuits in turn accused such priests of putting too much trust in the Protestant State, which was unlikely to reward their disruptive loyalty with religious toleration. These acrimonious splits at home spilled over to the colleges and religious houses in mainland Europe.

In 1595, more than half of English students at Rome revolted against their Jesuit superiors, complaining about the domineering ambitions of the Society of Jesus in England and their tyrannical running of the English College, where they were allegedly ‘seeking to rule [the students] by fear rather than by love, fostering divisions and strife among them in order to rule them more easily’.[3] The students demanded nothing less than the removal of Jesuits from the management of the College and the restoration of the old rules. They wanted the Pope to intervene and Cardinal Sega was eventually called to preside over a visitation in late 1595. Some months later, he produced a detailed report, confirming that the situation at the College was indeed unbearable, but firmly taking the side of the Jesuit administration.

The wider political implications and background machinations to these tumults, which lasted for a few years, until Robert Persons was appointed Rector in spring of 1597, have been extensively discussed by historians.[4] But what I find particularly interesting about Cardinal Sega’s report is the light it throws on the recent Carnival festivities.

Complaining about the Rector Fioravanti, the students claimed that

At the last Carnival, after a sumptuous dinner, at which he [Rector] entertained his favourites most liberally, he introduced buffoons and dancers into the College, and even compelled the students, despite their reluctance, to dance until midnight.

Foley, Records of the English Province, vol. 6, p. 22.

Our expectations are curiously challenged. Upon reading Southwell’s Festa mobilia we assumed that the students might have appreciated the licence for the late-night capering in the refectory. We were wrong. Clearly, at least some of them found playing and dancing inappropriate and even felt constrained by their superiors to continue until late in the night. Understandably, the Jesuits’ view on the matter was rather different:

(1) The sumptuous banquet consisted of some game or pies which the Italians call pasticcio, (2) which were served up in the Refectory, at the public table, not at all privately, as the attendants can bear witness. (3) They were not bought out of the College funds, but were a gift bestowed as a treat to the students, by a prelate who is one of the Rector’s friends; (4) nothing took place unbecoming our Seminaries, or which is unusual here; (5) they begged the Rector with all earnestness to grant them these things. And as they wished, according to their wont at home, to get up a dramatic entertainment for their fellow-countrymen, they vied with each other in the eagerness of their demands for costumes, scenery, and the other necessary matters, of which they now make a ground of accusation. […] As to the further charge, that on one occasion the students were forced to dance, and were kept dancing till midnight, it is untrue, as numbers can testify. Rather have they on certain occasions compelled the Rector to come to the common hall to receive their vote of thanks; his indisposition, however, hindered him from being present at their recreations.

Foley, Records of the English Province, vol. 6, pp. 41-42.

Southwell’s document seems to broadly support some of the details found in the response of Jesuit Fathers. And yet, the accusation of the students, however spurious and marginal it might seem, should be taken seriously. It is fascinating to see that when push came to shove, playing and dancing at Carnival suddenly mattered, forcing Jesuits to justify it! Whatever the truth, the students’ accusations reveal the Achilles’ heel of the ‘sanctified Carnival’ and Jesuit fondness of drama. However honest and seemly, dancing and acting were never quite without risk, especially in a college environment. Recreations could easily run out of hand, offend and cause scandal, particularly if those present at the entertainments were of somewhat uncharitable disposition. The irony is that in 1595, it was the seminarians themselves, the main recipients of Rector Fioravanti’s liberality, who suddenly saw it politic to accuse the Jesuits of promoting immorality.

[1] For more on the history of the English College, see Michael E. Williams, The Venerable English College Rome: A History (Leominster: Gracewing, 2008, 2nd ed.) and Maurice Whitehead, ‘“Established and putt in good order”: The Venerable English College, Rome, under Jesuit Administration, 1579–1685’, in Jesuit Intellectual and Physical Exchange between England and Mainland Europe, c. 1580–1789: “The World is our House?”, ed. by James E. Kelly and Hannah Thomas (Leiden: Brill, 2019), pp. 315-336.

[2] Peter Reitbergen, Power and Religion in Baroque Rome: Barberini Cultural Policies (Leiden: Brill, 2006), p. 11.

[3] Henry Foley, Records of the English Province of the Society of Jesus, vol. 6 (London: Burns and Oates, 1880), p. 20.

[4] Most recently for example by Peter Lake and Michael Questier in All Hail to the Archpriest: Confessional Conflict, Toleration, and the Politics of Publicity in Post-Reformation England (Oxford: OUP, 2019), see chapter 3 in particular.